A commonly-used quote from John Shepherd states, “Managing fisheries is hard: it’s like managing a forest, in which the trees are invisible and keep moving around.” This is particularly true for highly migratory species like sharks, for which the full range is often poorly understood even for the most well-known species. In the past, fish movements were usually defined by the time of year a species is present in an area where they’re easy to observe. Telemetry and fishery surveys have gone a long way in telling us where else a species might travel when not within sight, but it’s impossible to tag every single shark, know what’s going on at a survey site when no one’s looking, or even to make sure research efforts are encompassing the full range of the species. To further complicate things, a species’ range might differ wildly between seasons and between males and females.

To figure out where your target species is actually distributed, you have to take the information that you do have (survey catches, fishery landings, fishing effort distribution, telemetry detections, etc.) and do a lot of math (sometimes with lots of assumptions). With any luck, the data on were the species has been found can help identify other areas where it also might be found. In a newly-published paper first-authored by Andrea Dell’Apa with Maria Grazia Pennino, Chris Bonzek, and me, we did exactly that for the second most commonly-landed shark in U.S. fisheries.

The Smooth Dogfish (Mustelus canis) is a fairly common coastal shark endemic to the North American Atlantic coast. These sharks reach a maximum size of five feet and feed mostly on small crustaceans like crabs and shrimp, but from personal experience I can attest to them being much more wily and powerful than should be necessary for that lifestyle (most of my cases of shark burn have come from this species). They also have the distinction of being second only to the Spiny Dogfish (less closely related than you’d think) in numbers landed in U.S. shark fisheries. While this in and of itself isn’t necessarily a bad thing and both Spiny and Smooth Dogfish fisheries have been assessed as avoiding overfishing, Smooth Dogfish have the dubious honor of being exempt from the U.S. ban on removing fins at sea. With all this fishery management attention you’d think most aspects of Smooth Dogfish ecology would be pretty well-known, but aside from some studies on local movements and identified nursery habitats, little is actually known about where these sharks go when not in estuaries, or how the environment influences their distribution. To our knowledge, this hasn’t been attempted with this species before.

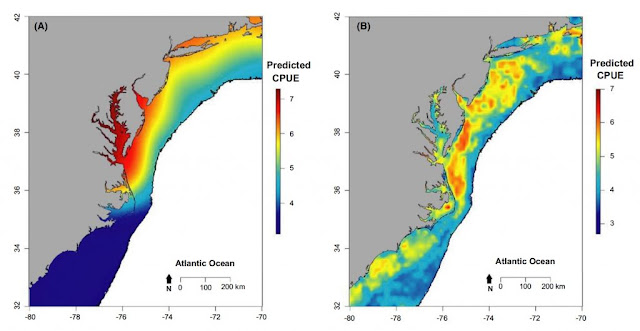

To get a better idea of where Smooth Dogfish are distributed, we took catch data from the Northeast Area Monitoring and Assessment Program (NEAMAP), which runs a nearshore trawl survey based out of the Virginia Institute of Marine Science. Smooth Dogfish are among the most commonly-encountered elasmobranchs on this survey, making it an ideal data source for both numbers and associations with environmental data. The cruise data gave us the numbers of Smooth Dogfish caught per trawl (the catch per unit effort, or CPUE) and catch locations, which were combined with environmental variables from other data sources including satellite-based remote sensing data and bathymetry maps to identify the ranges of those variables that were associated with higher shark numbers. Armed with this information, we could then use statistical modeling to predict what the CPUE should be across the whole U.S. Atlantic continental shelf based on the environmental conditions, season, and sex. To account for seasonal migrations, we modeled spring and fall CPUE separately, and we separated out males and females to account for differences between the sexes.

We used hierarchical Bayesian modeling to make our maps of predicted Smooth Dogfish catch. Without getting too far into the weeds, this type of modeling allowed us to account for both high numbers of survey sites where no sharks were caught and the tendency of sites where Smooth Dogfish were caught to occur near each other. These issues can affect model accuracy and are commonly-encountered when dealing with relatively rare and highly mobile species like most sharks.

|

| Maps of male Smooth Dogfish catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE, sharks per trawl) predicted using catch and environmental data from A) spring and B) fall. From Dell’Apa and friends (2018). |

|

| Maps of female Smooth Dogfish catch-per-unit-effort (CPUE, sharks per trawl) predicted using catch and environmental data from A) spring and B) fall. From Dell’Apa and friends (2018). |

The results of all this modeling showed differences both between seasons and sexes in where you should expect to find Smooth Dogfish. Males were found at relatively low salinities and shallow depths during the spring, and at temperatures less than 15 °C and mid-level bottom rugosity (basically an index of how rough the seabed is) during the fall. Females were caught in greater numbers at more shallow, rugose areas of the seafloor during the spring, and areas of relatively low salinity and mid-range chlorophyll-a concentrations during the fall. Mapping these habitat preferences showed that both females and males are distributed widely along the continental shelf north of the mouth of Chesapeake Bay and Delaware Bay during the spring while males are distributed considerable farther north (with an apparent hot spot along southeastern Cape Cod that calls for further investigation by fishery scientists) than females during the fall.

Aside from improving knowledge of where Smooth Dogfish are distributed, our findings have some very specific applications for fishery management. When trying to keep a fish stock sustainable, it’s often effective to limit fishing effort on mature females (referred to as “spawning stock biomass” in fisheries science) so they can survive to reproduce. For long-lived species like most sharks, a targeted fishery landing mostly males is arguably the more sustainable option. Sorry fellow dudes, when it comes to sustainable fisheries we’re just more expendable (and if you feel threatened by that I have bad news for you about differences between sexes in size and trophic level among many shark species). What our findings suggest is that during the fall a male-only fishery for Smooth Dogfish may be possible in southern New England, which would allow fishermen to continue working while giving the mature females a break.

This paper shows how, thanks to advances in scientific surveys, environmental monitoring, and statistics, we’re getting better and better at counting those invisible highly migratory “trees”. Or at least predicting where they should be.

By C. W. Bangley

This post was also published in: http://yalikedags.southernfriedscience.com/mapping-a-smoother-fishery-for-smooth-dogfish/

Cited Reference

Dell’Apa, A., M. G. Pennino, C. W. Bangley, and C. Bonzek. 2018. A hierarchical Bayesian modeling approach for the habitat distribution of Smooth Dogfish by sex and season in inshore coastal waters of the U.S. Northwest Atlantic. DOI: 10.1002/mcf2.10051